The Day the Flame Was Lit

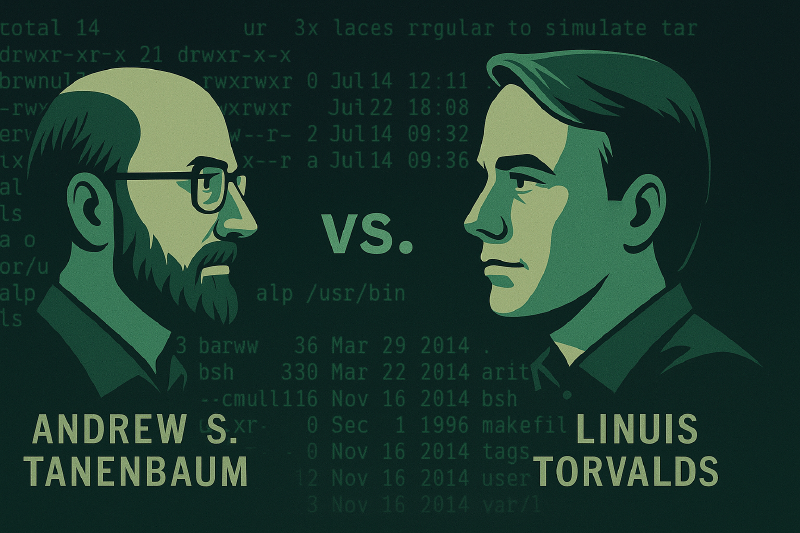

January 1992. Somewhere in the primordial swamp of Usenet, in a corner called comp.os.minix, Professor Andrew S. Tanenbaum, father of MINIX and patron saint of academic order, drops a bomb: “Linux is obsolete.”

That sentence, typed in plain ASCII and pure arrogance, lands squarely on the screen of a 22-year-old Finnish student named Linus Torvalds. His reply is calm, sarcastic, and surgical. Thus begins one of the first great Internet flame wars, and accidentally, a philosophical debate that would shape decades of computer design: microkernel versus monolithic kernel, Platonic order versus evolutionary mess.

Before the next act begins, the reader needs a breath—the tempo has been rapid-fire. Let’s pause, step back, and let the dust of that digital explosion settle before we enter the worldviews of the two men who started it.

Two Worlds, Two Faiths

Tanenbaum wasn’t just an academic; he was the academic. His 1987 MINIX was a model organism, tiny, elegant, portable, modular, a teaching tool meant to show how systems should be built. It wasn’t supposed to conquer the world, it was supposed to be clean.

Torvalds, learning from MINIX, found it slow, clunky, and overprotected, like trying to drive a sports car that keeps asking for permission to change gears. So he wrote his own kernel, not to overthrow academia but because he wanted something that actually worked on his 386. The result was a monolithic beast, everything running in one address space, blazing fast, and gloriously naive.

The difference between MINIX and Linux wasn’t just architecture, it was anthropology; a shift from laboratory precision to ecological improvisation that deserved a breath between metaphors. MINIX was the laboratory, a sterile, elegant habitat where every process knew its place and isolation was virtue. It was designed for control, safety, and didactic perfection.

Linux was the jungle, noisy, messy, adaptive. A living ecosystem of modules, bugs, and stubborn survival. Tanenbaum built a cathedral. Torvalds unleashed a zoo.

History’s punchline is deliciously ironic. The clean academic kernel ended up buried deep inside Intel chips as a closed-source firmware (the Intel Management Engine), while the “dirty hobby project” became the backbone of the modern Internet. The lab became a ghost in the machine, the jungle took over the world.

The microkernel dream was intoxicating: a minimal core where everything else lived in user space, talking through message passing. Fault isolation, portability, security, textbook beauty. In theory it was perfect; in practice it was molasses. CPUs of the time choked on context switches, and message queues became swamps. The idea was right, but the timing was disastrously wrong, like publishing a masterpiece before the invention of paper.

The Dispute, Word for Word

The flame war wasn’t a tantrum, it was a duel in syllogisms. Tanenbaum opened with academic thunder: “I consider any monolithic kernel obsolete.” In his mind the future belonged to modular microkernels, elegant little Lego sets of computing.

Torvalds replied with Nordic mischief: “Portability is for people who can’t write new operating systems.” Translation: stop future-proofing the present to death. Build what runs now.

Tanenbaum wanted an immaculate machine, where each component could be verified like a theorem. Torvalds preferred an evolving organism, ugly but alive. One trusted theory to lead practice; the other trusted practice to expose truth.

Tanenbaum doubled down: “I designed MINIX for teaching, not for production use.” It was a pedagogical cathedral, not a war engine. Torvalds, ever the anti-hero, shot back: “I do this just as a hobby, won’t be big and professional like GNU.” Modesty as a weapon. Behind that line, though, was a declaration of creative independence, the freedom to build without asking permission.

Tanenbaum predicted that RISC architectures would soon rule the earth, and Linux, chained to x86, would die a quaint fossil. Linus disagreed, betting on the messy reality of standard hardware. Decades later, both turned out half-right: portability won the war, but Linux conquered the decade.

The flame eventually grew philosophical: who decides what “good architecture” means, the professor or the community? The model or the mutation?

Linux went all in on chaos. Everything from drivers and memory to network stacks shared the same address space, merging speed with danger. There was no bureaucratic message passing, only raw efficiency. Fast, risky, and shockingly democratic, it turned necessity into rebellion. Torvalds summarized the creed:

“Theory is nice, but if it doesn’t work on my PC, I don’t care.”

What emerged wasn’t an architectural manifesto but an evolutionary experiment. The kernel became not a cathedral but a bazaar, noisy, decentralized, and self-correcting. Bugs weren’t sins; they were mutations waiting to be refined by use.

Tanenbaum accused Linux of being a dinosaur. Torvalds called it a mammal. Evolution, he argued, doesn’t read whitepapers, it adapts. The rise of Linux became the field experiment that proved it: survival favors the mess that runs.

The moral aged well: purity is expensive, life is dirty but functional. Every system lives in the tension between elegance and entropy. Some are designed to be right, others are designed to survive.

Beyond the War: Unlikely Convergences

Ironically, both sides won by cross-pollination. Microkernels evolved into QNX, Mach, seL4, under the hoods of macOS, iOS, and cars. Linux, once the monolithic rebel, learned modularity, dynamic drivers, namespaces, containers. The borders blurred; the flame cooled, but never went out.

Today’s architectures are hybrid creatures: clouds running on modular monoliths, containers on layered kernels, abstractions over chaos. The 1992 debate still hums beneath every API call.

The final section lands with satisfying cadence, balancing reflection and precision. The rhythm swells through contrast—order versus emergence, purity versus pragmatism—then releases gracefully with the admission that perfection is an illusion. The tone remains steady, closing the argument like a well-tuned loop rather than a curtain drop. The Tanenbaum–Torvalds exchange outgrew its own subject. It stopped being about kernels and started being about creation itself: order versus emergence, purity versus pragmatism, professors versus hackers.

In code, as in life, there is no perfect architecture, only the ones that keep running. One guarded the form, the other lit the fire. Both were right, and both are still arguing in our commits.

That argument in ’92 wasn’t about the past, it was the spark of our hybrid age, where every architecture is a truce between theory and survival.

References and Further Reading

- O’Reilly: Appendix A – The Tanenbaum/Torvalds Debate

- Carnegie Mellon University: LINUX’s History by Linus Torvalds

- Google Groups Archive: comp.os.minix discussion thread

- Scribd: Tanenbaum–Torvalds discussion PDF transcript

These sources preserve the historical conversation and context of the original flame, though completeness and accuracy may vary among archives.